Few plays capture Chicago (or at least, one cruddy corner of Chicago) as well as David Mamet’s 1975 classic American Buffalo — and director Amy Morton’s new staging of the drama at Steppenwolf Theatre is top-notch. Authentic Chicago dialogue, desperate men cooking up criminal schemes to get rich, piles and piles of junk. And three actors (Tracy Letts, Francis Guinan and Patrick Andrews) delivering realistic, visceral performances.

Few plays capture Chicago (or at least, one cruddy corner of Chicago) as well as David Mamet’s 1975 classic American Buffalo — and director Amy Morton’s new staging of the drama at Steppenwolf Theatre is top-notch. Authentic Chicago dialogue, desperate men cooking up criminal schemes to get rich, piles and piles of junk. And three actors (Tracy Letts, Francis Guinan and Patrick Andrews) delivering realistic, visceral performances.

In case you know Letts only as a playwright (from works such as his Pulitzer winner August: Osage Country), he takes this opportunity to remind everyone that he’s an actor, too. Playing the garrulous loser Teach, Letts let loose rivers and rivers of Mamet’s dialogue — and then he brings some powerful, almost unexpected emotion to the climatic scene. Junk-shop owner Don has a strained friendship with Teach, and you wonder sometimes why Don doesn’t kick this guy out of his life. In his performance as Don, Guinan plays with that feeling of being trapped — trapped with the friends you have, including the exasperating ones like Teach. Portraying Bobby, the young protégé of these low lifes, Andrews conveys his character’s slow mental capacities without playing it for laughs, revealing what feels like a real person behind a seemingly dim-witted face.

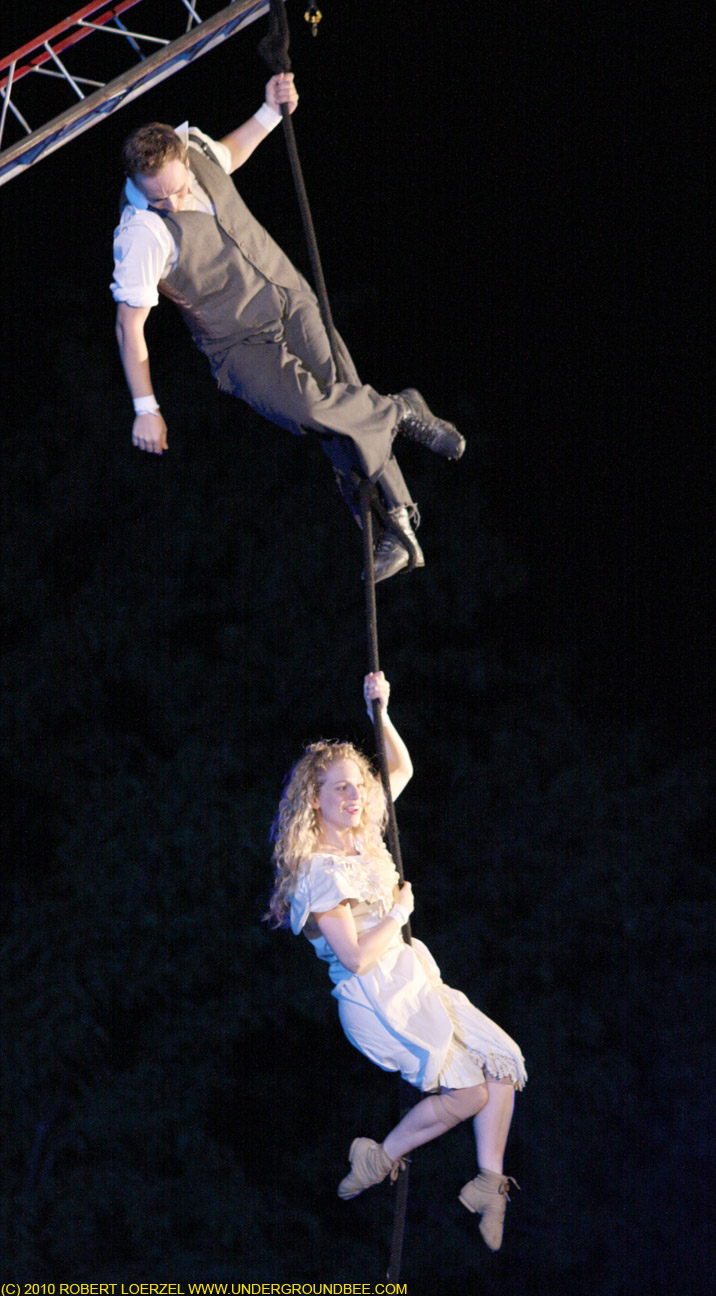

Together, they’re a terrific ensemble. The show is funny where it needs to be, and it’s tragic and moving in its debris-littered denouement. Mamet’s junk shop clatters to life at Steppenwolf. (Photo by Michael Brosilow.)

(J.J. Johnson, Mike Nussbaum and William H. Macy (left to right) in the Goodman Theatre Stage 2’s 1975 production of American Buffalo. Photo courtesy of the Goodman Theatre.)

(J.J. Johnson, Mike Nussbaum and William H. Macy (left to right) in the Goodman Theatre Stage 2’s 1975 production of American Buffalo. Photo courtesy of the Goodman Theatre.)

For whatever reasons, American Buffalo flopped last year when the Goodman Theatre’s Robert Falls directed it on Broadway with an all-star cast (John Leguizamo, Cedric the Entertainer and Haley Joel Osment). At the time, I posted the following essay at the Huffington Post looking back at the reviews American Buffalo received when it was performed for the first time in 1975.

American Buffalo came and went pretty damn fast on Broadway this fall. The reviews were not exactly glowing for director Robert Falls’s revival of David Mamet’s drama, which is widely regarded as one of the playwright’s best plays. It’s worth remembering, though, that critics did not greet American Buffalo with universal acclaim when it first appeared in 1975.

It was one of those plays that provoked extreme reactions. At those early performances, some reviewers believed they were witnessing an all-time classic. Others just saw a piece of theatrical garbage. And even as the play moved to Broadway, receiving the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award as the best American play of the 1976-77 season, the reviews were mixed — very mixed.

Those of us who missed the premiere of American Buffalo three decades ago are left to imagine what it was like from reading Mamet’s script, seeing a new performance or looking back on the wildly divergent reviews that critics wrote in the 1970s. The fleeting, ephemeral nature of theater is part of makes it so special as an art form. As they say, you had to be there.

The earliest champion of American Buffalo was Richard Christiansen, who was theater critic for the Chicago Daily News at the time. Christiansen, who later wrote for the Chicago Tribune, is the author of A Theater of Our Own: A History and a Memoir of 1,001 Nights in Chicago, which includes his account of the days when Mamet’s plays appeared onstage for the first time.

Back in October 1975, when Gregory Mosher directed American Buffalo at the Goodman Theatre’s Stage 2, Christiansen wrote a rave review: “American Buffalo illuminates the truth with humor, suspense and a keen insight into the human spirit,” he said. “Mamet’s mesmeric dialog … turns gutter language into vibrant music … The play is a triumph for Chicago theater — and a treasure for Chicago audiences.”

But Mamet’s foul language and low-life setting — a Chicago junk shop where three guys ineptly scheme to steal a coin collection — turned off other critics. Reviewing the play for the classical radio station WMFT, Claudia Cassidy said it took “a very long, very dull time” to reach its climax. She added, “Does the Goodman’s Stage 2 really believe that filthy language is a substitute for drama?”

“At this point it is just a dreary slice of life that needs tightening, focusing and clarifying,” Glenna Syse wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times. “Shortening? Yes, but if they took out all the four-letter words, it would last ten minutes and somewhere along the line it needs an ending.”

“One can sense the direction in which Mamet wanted to go, although he hasn’t yet finished or polished his play,” Roger Dettmer wrote in the Chicago Tribune. “The machismo epithets of Uptown become tediously dirty (which they are in real life). But drama is a distillation of life, not mere eavesdropping. American Buffalo right now is about 20 usable minutes of a play that Mamet needs to edit, expand, enliven, and point in some direction.”

Writing in the Chicago Reader, Bury St. Edmund found much to admire in American Buffalo, but said it needed to be cut and restructured. “American Buffalo, if I may paraphrase a paraphrase David Mamet used in the Reader a few weeks back, is just like a play, only longer,” he wrote. “Once the fat is trimmed and some hustle is added to the performance, it will be more clearly seen for what it is, an excellent piece of theater by someone who’s got something to say and a god-damn original way of saying it.”

Whatever the critics said, crowds filled the theater. In its first three weeks, American Buffalo earned $2,878.18 — a modest sum by today’s standards, but a record at the time for the Goodman’s Stage 2.

The play moved to Mamet’s theatrical home base, the St. Nicholas Theater, for another run on Dec. 21, 1975. A press release noted, “A work-in-progress in its original production, American Buffalo has undergone several revisions by playwright Mamet.” Two of the original cast members, William H. Macy and J.J. Johnston, reprised their roles, while Mike Nussbaum took over the part previously played by Bernard Erhard.

The Chicago critics were more enthusiastic this time. Writing in the Lerner Skyline, Ron Offen said, “with this production … they have coined a sound piece of theater that is silver shiny, if not gold.” In the Tribune, Linda Winer wrote, “Mamet’s gift is character language, here almost poetic in its patter profanity, the dry stylized rhythms and rich reality of the sounds.”

Christiansen saw the drama for a third time, and still found it to be a rich experience. He praised Mamet’s revised ending. “The play itself has been slightly revised (and improved) by Mamet, and it remains the best work yet to come from the best playwright Chicago has produced in this decade,” Christiansen wrote.

When American Buffalo moved to Broadway in 1977, some critics called it one of the most original plays they’d seen in a long time. In New York magazine, Alan Rich wrote: “David Mamet’s name can be firmly installed in that small galaxy of young native playwrights who have something to say and the technique with which to say it.” Clive Barnes of the New York Times declared, “This is Mr. Mamet’s first time on Broadway, but it will not be his last. The man can write.” And Martin Gottfried of the New York Post said, “It isn’t often that a play with the dynamic intensity of American Buffalo comes to the Broadway theater.”

For his part, Christiansen believed the Broadway production, directed by Ulu Grosbard, was even more powerful than the earlier performances in Chicago. “Mamet has revised the script and substantially strengthened the ending, clarifying and deepening its dirge for the lives of the play’s three lost human beings,” he wrote.

American Buffalo continued to receive scathing reviews from some quarters. In the New York Daily News, Douglas Watt concluded: “In spite of their lively talk and Ulu Grosbard’s effective staging, the three dimwits become increasingly boring; and their stupidity and fumbling efforts, however realistic, simply add to the confusion of a play that promises much more than it ever delivers.”

And The New Yorker opined: “It is a curiously offensive piece of writing, less because of the language of which it is composed … than because it is so presumptuous. The playwright, having dared to ask for our attention, provides only the most meager crumbs of nourishment for our minds.”

Critics from outside New York were especially harsh. “What a letdown!” wrote Richard L. Coe of the Washington Post. “Is this drama? … I didn’t believe much of the dialogue, accurate as snatches of it may be. In fact, I found Mamet rather patronizing of his characters, mocking their ignorant pretensions from a perch of superiority. … to label, as some have, this leaden excursion into meanderings of inarticulate, failed criminals as ‘the best American play of the year’ is merely to reflect what a trashy theater season New York has had. I share the view of the others in this split critical decision, who found that ‘this coarse twaddle adds up to meaning zero.'”

“All it suggested to me was three simple minded hoods planning a robbery,” Tony Mastroianni wrote in the Cleveland Press. “If there is any message in the play, it is probably that life is rotten, even for rotten people … As for the play — it is pretentious, promising something under its rawness and delivering nothing.”

“The playwright’s observations (psychological, sociological, etc.) are too superficial to waste time upon,” wrote John Beaufort of the Christian Science Monitor. “This is a very thin slice of lowlife.”

“A trashy, odious play,” wrote Associated Press critic William Glover. “Dialog consists mostly of profanity and repetitive stretches of the low and patronizing humor that some people find in overhearing ignorant and inarticulate unfortunates. … In his favor, Mamet has a tape-recorder fidelity at reproducing contemporary speech. His dramatic skill is limited, however, to attenuated skits. American Buffalo presumably attempts to make a coherent statement. All that it delivers is fulsome rubbish.”

Even when the reviews were bad, the staffs at the Goodman Theatre and St. Nicholas Theater dutifully clipped all those articles and saved them in files — which are now in the Special Collections room at Chicago’s Harold Washington Library.

This fall’s production at the Belasco Theatre had a highly talented director, Robert Falls, at the helm. Falls is the artistic director of Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, and he also happens to be an old friend of Mamet’s. And he’s directed some notably great shows over the years. The new American Buffalo featured an all-star cast. Or as Ben Brantley of the New York Times put it, a “mixed-nut ensemble” — John Leguizamo, Cedric the Entertainer and Haley Joel Osment. Brantley’s review opened with the sort of scathing comment that makes you almost involuntarily exclaim “Ouch!” He wrote: “Ssssssssst. That whooshing noise coming from the Belasco Theater is the sound of the air being let out of David Mamet’s dialogue. Robert Falls’s deflated revival of Mr. Mamet’s American Buffalo … evokes the woeful image of a souped-up sports car’s flat tire, built for speed but going nowhere.”

The show lasted less than a week after the press opening. And alas (or should I say “thankfully”), I missed my chance to see it. Falls’ other directorial efforts have been so strong it’s hard to believe this one was such a flop, but I guess I’ll never know. One wonders if the critics who hated American Buffalo in the 1970s have changed their minds. Apparently, this production was not the test case to answer that question.

DAVID DANIELL

DAVID DANIELL