First of all, let me stipulate that Sonic Youth is a great band. I’ve enjoyed their music for many years. Their new record, The Eternal, is a darned good one, and they played an excellent show Saturday night at the Vic Theatre. You can see my review of that concert on the Web site of the Southtown Star newspaper.

One thing you can’t see here on my blog, however, is the sort of photo gallery I post after most concerts. I did not take any pictures of Sonic Youth. The reason is that I refused to sign a legal contract that the band’s management required photographers to sign before receiving photo credentials.

Here’s a little bit of background to help you understand this issue. I’m a freelance journalist, and I take photos at about 100 concerts a year (more than 300 if you count all the opening bands and festival acts). I am doing this photography largely as a hobby, rarely getting paid anything for it. I enjoy seeing live music and taking photos. Many of the concert venues I attend, including Schubas, the Hideout and the Empty Bottle, usually let anyone take photos for as long as they want. Sometimes I get into these shows for free on the guest list, and sometimes I pay. At other venues, including Metro, the Riviera and the Vic, you generally need to get photo credentials from the band, label or venue to take pictures with an SLR camera, and you’re often restricted to taking photos during the first three songs.

I post photos from the concerts I attend here on this blog on also on flickr. I post anywhere from a few pictures to 20 or 30 of a band, and I leave the pictures posted on my Web site indefinitely. Bands, labels, online publications, newspapers and magazines sometimes ask permission to run my photos, usually asking for higher-resolution images — and usually offering nothing but a photo credit line in return. More often than not, I agree. Once in a while, someone offers actual money for the photos.

Some concert photographers do make money, of course. Maybe I will eventually. I daresay that many of the other photographers I know or encounter at concerts in Chicago are in a similar situation. With the rise of digital cameras, a lot of people (including me) realized we could take photos at concerts and thought, “Why not?” At times, the proliferation of photographers snapping away at a concert can be annoying, and I suppose I’m just as much to blame for that as anyone. (Hey, I do try to be as unobtrusive as possible, keeping aware of the fans standing or sitting near me.) With all these photographers out there (at least a few of whom have decent-enough SLR cameras and lenses to get good shots at dark venues, all of which will run you thousands of dollars), it’s becoming hard to demand much compensation for your work. That’s the law of supply and demand.

A lot of us are glad to get free tickets, the chance to photograph a musician we admire, and a little bit of attention from people commenting on our photos. I certainly don’t feel entitled to get photo credentials for every concert. It’s been a great privilege to shoot pictures of some fabulous musicians over the last few years. I know there are times when I won’t make the cut because there’s a limit on how many photographers you can cram into the space in front of the stage. You can’t always get what you want, right?

Some musical acts now ask photographers to sign a legal agreement — often called a “release,” “waiver” or “contract” — before they get credentials to take photos at a concert. I believe this practice is more common with big-label artists than it is with independent musicians. Out of the 300 or so musical acts I’ve photographed over the past year, only three asked me to sign a legal agreement: Nine Inch Nails, Nick Cave and Sonic Youth.

Most of these agreements include a clause restricting how you can use the photographs you’ll take at the concert. This clause might say that the photos can appear in only one publication, and they might limit how long those photos can appear online. The agreement might also spell out some of the things you can’t do with the photographs — such as selling them or using them on merchandise like posters and T-shirts.

I can see why musicians want to prevent people from making money from photographs of them. That’s not something I’ve ever done, and I don’t have any interest in doing it without permission from the musicians. And even if I don’t try to profit from the images I’m posting, it’s hard to stop other people from grabbing those pictures and doing whatever they want with them. They’re not high-res images, however, and I doubt if anyone’s going to make much money selling a poster based on a photo lifted from one of my sites.

I suspect some musicians are trying to control their image by limiting the photographs that are out there online. That’s a lost cause. It’s too late to stop the proliferation of concert photos online. Even when the number of professional concert photographers is limited, other fans take pictures with their point-and-shoot cameras and cell phones. A lot of those photos invariably end up online.

And it’s not only a lost cause. Limiting the number of photos also hurts the musicians. The more photos of a band are out there, the more people are likely to discover that band. Fans enjoy seeing pictures of their favorite musicians, right? And how does the existence of all those online photos harm a musician? It’s all publicity and attention, which helps to raise a musician’s profile. Sure, not all of those photos are going to be great works of art or even flattering images, but there aren’t too many photographers going out of their way make musicians look bad.

Some musicians may be using these agreements for the simple reason that they don’t want to be distracted by photographers during their shows. Or they don’t want their fans to be annoyed by a bunch of photographers. I can understand this, but it’s something that’s usually dealt with by setting rules at the venue (such as that three-song limit) or just limiting the number of people getting photo passes.

Even though I think it’s silly for musical acts to ask photographers to sign agreements limiting the use of their pictures, I’ve agreed to sign some of these papers. When Nick Cave played last year at the Riviera Theatre, I included two publications on the form — this blog as well as the Southtown Star newspaper. I posted photos here and submitted one to the newspaper. When Nine Inch Nails played at Lollapalooza last year, I signed a similar deal, allowing me to post a picture for a limited time at the Southtown Star. I took photos but I did not end up publishing any.

Last week, I was excited at the prospect of photographing Sonic Youth. I was told I would be getting a photo pass, and I was planning to take a picture to run along with my review for the Southtown Star as well as a gallery of photos for Underground Bee.

But the day before the concert, one of the publicists for Sonic Youth’s record label, Matador, told me I would have to sign a waiver before getting photo credentials.

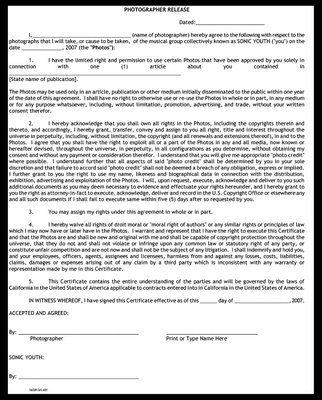

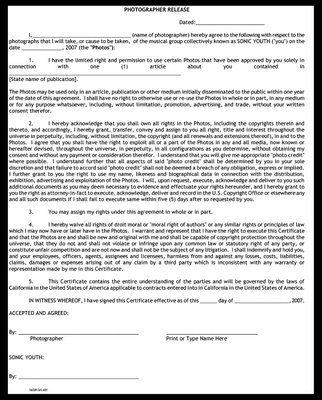

THE LEGAL AGREEMENT SONIC YOUTH ASKED ME TO SIGN:

The first part of the “photographer release” was pretty standard stuff, similar to what Nick Cave and Nine Inch Nails had demanded. This section said:

“1. I have the limited right and permission to use certain Photos that have been approved by you solely in connection with one (1) article about you contained in [State name of publication].

“The Photos may be used only in an article, publication or other medium initially disseminated to the public within one year of the date of this agreement. I shall have no right to otherwise use or re-use the Photos in whole or in part, in any medium or for any purpose whatsoever, including, without limitation, promotion, advertising, and trade, without your written consent therefor.”

OK, this was disappointing to me, but I could deal with it. I would have preferred getting permission to run photos on my blog as well as the newspaper Web site. And I’d prefer to run them for more than a year. Why take the photos down after a year? What purpose does that serve? So at this point in reading the contract, I was grumbling but still planning to sign it.

Then I got to the second section:

“2. I hereby acknowledge that you shall own all rights in the Photos, including the copyrights therein and thereto, and accordingly, I hereby grant, transfer, convey and assign to you all right, title and interest throughout the universe in perpetuity, including, without limitation, the copyright (and all renewals and extensions thereof), in and to the Photos.”

WHAT?!? Sonic Youth is going to own the copyright on my photos? Now, this was a whole new level of musicians seeking control over the work of photographers. I’d heard that Morrissey was making similar demands of photographers recently, but this was the first time I’d ever been asked to sign such a deal.

A little bit of additional background. As a freelance photographer, any photographs I take are my intellectual property. In most cases, if I’m working for a publication, that publication acquires the first rights or some limited rights to run my photos, but it does not become the copyright owner of my work. The situation is different for most staff photographers working on the payroll for newspapers and magazines. Their photos are considered “work for hire,” and in most cases, the publication itself owns the copyright.

There’s also something called publicity rights. The basic idea is that the person in the picture has publicity rights. This is what prevents someone like me from sticking a photo I took of Sonic Youth on a billboard endorsing Snickers bars or whatever. As I see the law (and I’m no lawyer or intellectual-property-rights expert), there is bound to be some tension between the photographer’s copyright on an image and the publicity rights of the person inside that image anytime you try to make a profit from the picture. But that’s a legal question for another day.

The one thing I do know is that any artist should be very reluctant to sign over a copyright on his or her work to anyone else, whether it’s a photograph, piece of music, book or whatever. When the University of Illinois Press published my book, “Alchemy of Bones,” in 2003, I made sure that the copyright was in my name. The idea that Sonic Youth would completely own all the creativity and work I put into my photographs was totally unacceptable. Why even bother taking the pictures? Now, if the band or record label was paying me to take photos and then keeping the copyright on the images, that would be another matter.

That second section of the contract went on:

“I agree that you shall have the right to exploit all or a part of the Photos in any and all media, now known or hereafter devised, throughout the universe, in perpetuity, in all configurations as you determine, without obtaining my consent and without any payment or consideration therefor.”

So, now the band is spelling out the fact that it could use my photos on album covers, posters, press releases or whatever it wants without paying me anything. That hardly seems fair, does it?

The legal agreement continues:

“I understand that you will give me appropriate ‘photo credit’ where possible. I understand further that all aspects of said ‘photo credit’ shall be determined by you in your sole discretion and that failure to accord said ‘photo credit’ shall not be deemed a breach of any obligation, express or implied.”

Well, gee, thanks for thinking of me. I’m so glad you might give me a photo credit… or might not.

There’s more:

“I further grant to you the right to use my name, likeness and biographical data in connection with the distribution, exhibition, advertising and exploitation of the Photos.”

OK, now I don’t know why the band would want to use my likeness. Maybe if I were a famous photographer. But if I were a famous photographer, I’d probably have enough clout to take pictures without signing this crappy deal.

The contract goes on … including a section saying that “I hereby waive all rights of droit moral or ‘moral right of authors’ or any similar rights or principles of law which I may now have or later have in the Photos.”

There was no way I was going to put myself into this sort of copyright servitude, so I told Matador Records that I refused to sign the legal agreement. I asked if I could still get a press ticket to attend the show without photo credential, so that I could write a review, and I did receive that.

I exchanged a few e-mails Friday with two publicists at Matador. They told me Sonic Youth’s management had insisted on using this legal agreement, and they said they would check to see whether it could be changed. I did not hear back from them after that, and went to the concert without a camera.

It’s particularly disappointing to receive this sort of treatment from a band like Sonic Youth, which has a reputation for its independent spirit. And based on everything I can see, the members of Sonic Youth really do seem to be nice people in addition to being talented musicians. I’m hoping they don’t realize how artist-unfriendly their photography waiver is. I would not be surprised if this legal agreement is an overreaction — an attempt to protect the band from unauthorized photography sales that goes too far. It’s a sledgehammer approach.

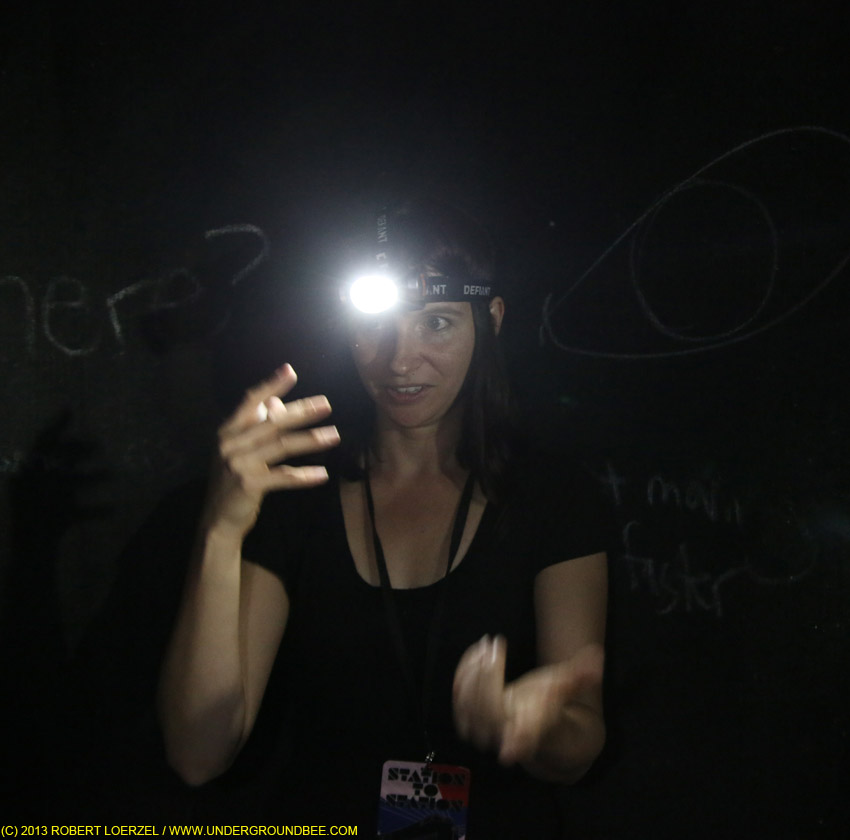

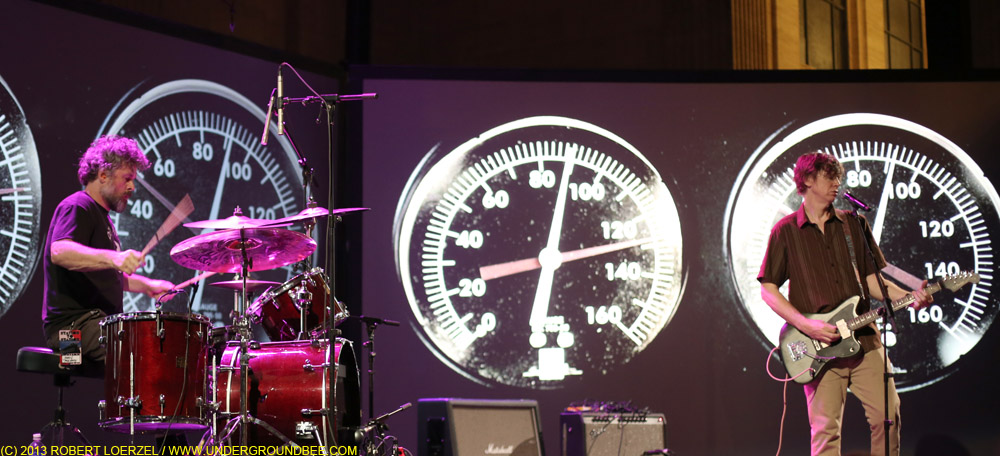

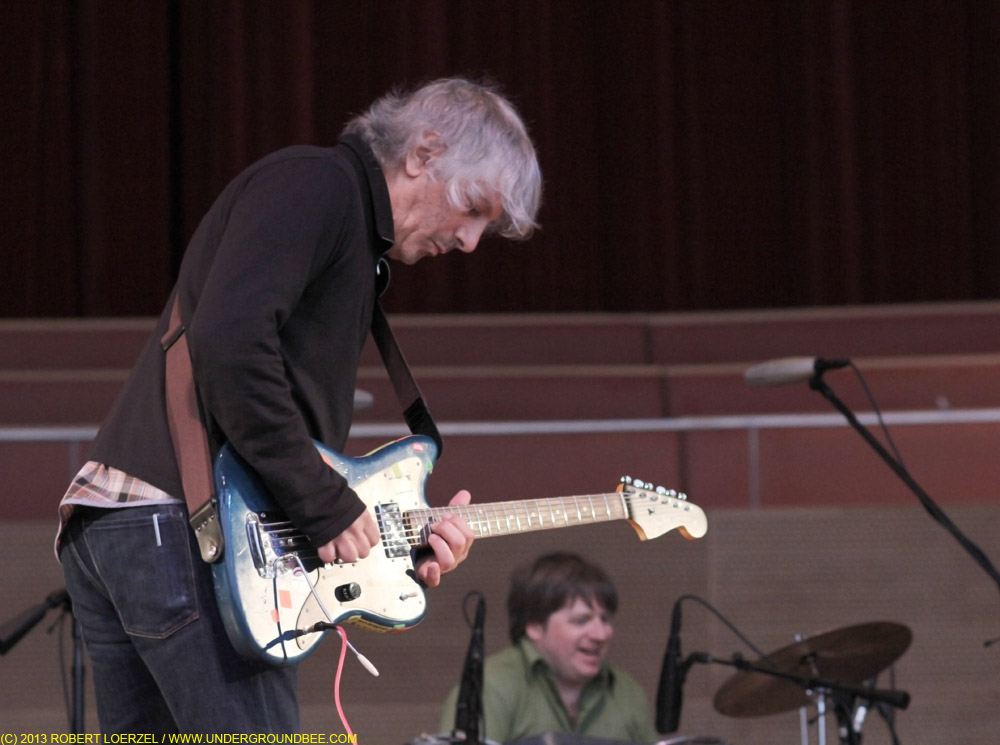

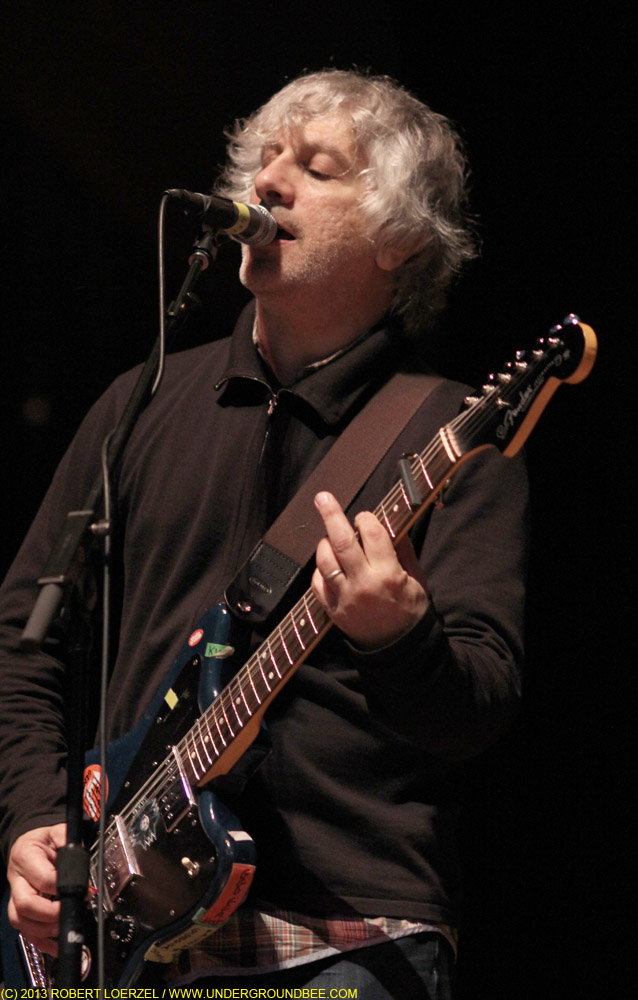

And so, in lieu of any photos from Saturday’s concert, I present some photos I took of Sonic Youth when they played at the 2007 Pitchfork Music Festival. The band let me and a bunch of other photographers take pictures that time without signing anything. Imagine that. I suppose these two-year-old photos (not my greatest work, I freely admit) are an example of the pernicious sort of old pictures floating around on the Internet, harming musicians by their very presence, which this legal agreement was designed to prevent. Here they are. I hope it doesn’t hurt too much, guys.

And so, in lieu of any photos from Saturday’s concert, I present some photos I took of Sonic Youth when they played at the 2007 Pitchfork Music Festival. The band let me and a bunch of other photographers take pictures that time without signing anything. Imagine that. I suppose these two-year-old photos (not my greatest work, I freely admit) are an example of the pernicious sort of old pictures floating around on the Internet, harming musicians by their very presence, which this legal agreement was designed to prevent. Here they are. I hope it doesn’t hurt too much, guys.