You had to be there. An audio recording of the International Contemporary Ensemble’s performances last weekend at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago might capture some of what happened, but to understand and appreciate what ICE was doing with Alvin Lucier’s compositions, you really needed to be inside that three-dimensional space. You needed to move around the museum’s fourth-floor atrium to feel the sound waves coming from various directions.

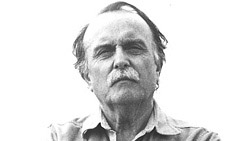

ICE devoted three concerts to the work of this innovative composer, the most extensive retrospective of Lucier’s work ever performed in Chicago. (Read Peter Margasak’s interview with Lucier in the Chicago Reader.) I attended Saturday’s concert.

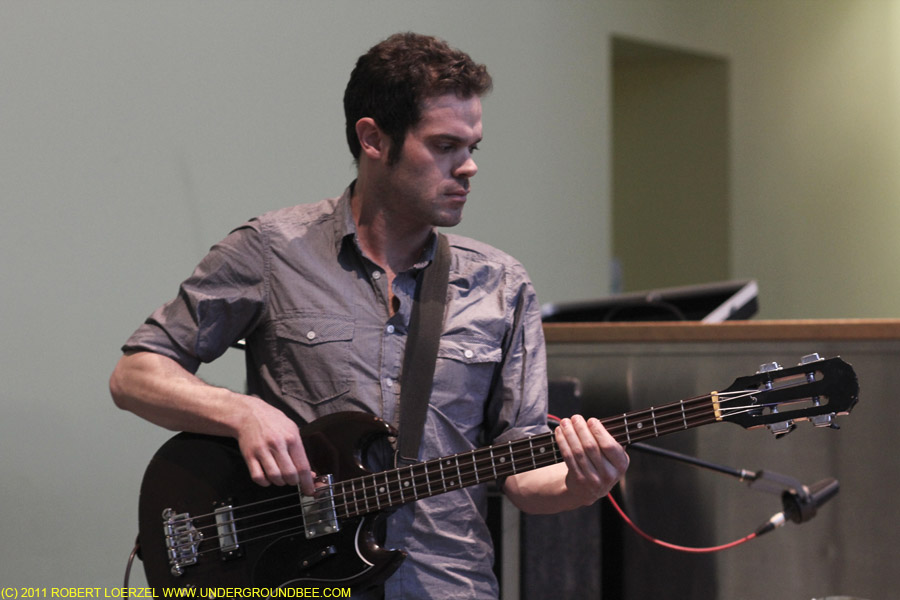

The closest thing to a piece of traditional music was Lucier’s 2013 work “Codex,” performed by soprano Tony Arnold and five musicians: David Bowlin on violin, Nicholas Masterson on oboe, Daniel Lippel on guitar, Katinka Kleijn on cello and Campbell MacDonald on clarinet. At times, it seemed like each of these players was expressing just one tiny note at a time: a plink of one string on the guitar, a wordless “ah” from Arnold, a tone from the oboe, and so on, with the notes overlapping to create the sense that they were sustaining. Was it just an illusion that this was a minimal skeleton of music? Or was it an illusion that this seemingly bare framework somehow revealed richer colors? It was a shimmering but mournful wonder.

Some of the other Lucier pieces performed on Saturday were more like sonic experiments than traditional compositions. Most striking was “Still and Moving Lines of Silence in Families of Hyperbolas” (1973–74, revised 2013), which featured two speakers at one end of the atrium emitting tones from pure wave oscillators. We were encouraged to walk around the room and experience the changes in volume level and vibrations where the waves from the two speakers came together. There was Lucier himself, leading a line of people slowly moving forward from the wall to experience the oscillations; I got in line and followed him. Musicians accompanied the oscillations. Just one note — C sharp — was struck on a marimba over and over. The soprano raised her voice and sang along.

That piece segued into “In Memoriam Jon Higgins” (1984), for clarinet and pure wave oscillator. The concert also included a duet between bassoonist Rebekah Heller and an electric lamp. And it ended with a piece that featured no live musicians at all: just a violin hooked up to wires and attached to a pole, surrounded by microphones and sound-sensitive lights.

Through it all, there was a remarkable feeling of calm in the room. You could sense the other people around you paying close attention to every nuance of noise. You could feel the physics of what makes music.

Sadly, I missed most of the Sonar festival, which seemed like a cool addition to Chicago’s September music lineup. Frost stood alone on the stage inside the Claudia Cassidy Theater, switching between his electric guitar and an array of electronics, including a laptop, as he made unsettling and droning noise. Frost created dissonant, almost overwhelming mountains of sound, including some looping repetitions that seemed to sample an animal’s growl and human breathing — familiar sounds that became strange and menacing in this new context.

Sadly, I missed most of the Sonar festival, which seemed like a cool addition to Chicago’s September music lineup. Frost stood alone on the stage inside the Claudia Cassidy Theater, switching between his electric guitar and an array of electronics, including a laptop, as he made unsettling and droning noise. Frost created dissonant, almost overwhelming mountains of sound, including some looping repetitions that seemed to sample an animal’s growl and human breathing — familiar sounds that became strange and menacing in this new context.  The first composition ICE performed Saturday is a perfect example of the sort of music it’s well-positioned to play: Pierre Boulez’s Memoriale (…explosante-fixe…originel), a 1985 piece for flute and eight instruments. Flutist Claire Chase is ICE’s offstage leader, and she often takes the lead onstage, too. She dominated the Boulez piece, but conductor Jayce Ogren kept the flute and strings in fragile, delicate balance.

The first composition ICE performed Saturday is a perfect example of the sort of music it’s well-positioned to play: Pierre Boulez’s Memoriale (…explosante-fixe…originel), a 1985 piece for flute and eight instruments. Flutist Claire Chase is ICE’s offstage leader, and she often takes the lead onstage, too. She dominated the Boulez piece, but conductor Jayce Ogren kept the flute and strings in fragile, delicate balance.