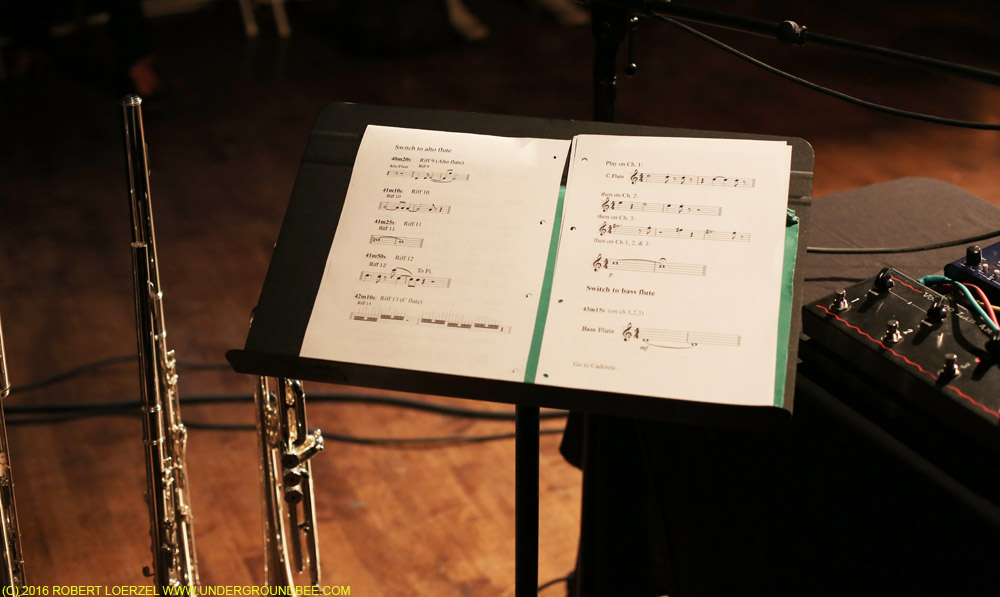

My photos of Rhys Chatham’s performance on Friday, May 20, at Constellation, along with a picture of opening act Natural Information Society.

The Necks at Constellation

The Necks have been improvising beautiful music for many years now. You might call them a jazz trio — after all, they do follow the standard lineup of instruments you’ll see in many jazz trios: piano, bass and drums. But these Australian musicians create their own distinctive sort of music, as they demonstrated Sunday, March 27, in a breathtaking performance at Constellation. They played two sets — each consisting of a single, uninterrupted piece of music that steadily built up from the smallest and quietest of musical gestures. At the very beginning, it was just Tony Buck flicking a brush on one of his drums. And then Lloyd Swanton joined in, fingering the strings of his upright bass with a rumbling musical gesture that fit in perfectly with the brushing. Finally, Chris Abrahams tenderly touched the keys of the piano, creating a circling pattern of notes. These minimalist motifs gradually transformed, growing in volume and intensity, but a steadiness remained at the heart of the music — each musician closely following the lead of the others but then pulling the trio in a slightly new direction. It was a wonder to see and hear.

Spunk at Constellation

The concert Wednesday, March 16, at Constellation was the first U.S. performance by Spunk, a quartet of Norwegian woman who have been improvising music under that name since 1995. Actually, as it turned out, it wasn’t quite a performance by the full group; cellist Lene Grenager wasn’t able to play due to an illness. But the rest of Spunk — Maja Solveig Kjelstrup Ratkje on voice and electronics; Kristin Andersen on trumpet, recorders and flutes; and Hild Sofie Tafjord on French horn and electronics — played as a trio, making some gloriously peculiar sounds. The absence of cello may have caused the mix to lean more heavily toward electronics, but it was really all about the way all of the noises blended together into shapes and textures. Bassoonist-composer Katherine Young opened the concert with similarly strange explorations of imaginative soundscapes.

Frequency Series Festival of Chicago New Music

“New music” seems to be catching on lately as a label for the stuff that we used to call “20th-century music.” Neither label really works, but what else should we call the new music composed for classically trained musicians? Whatever you call it, it’s thriving in Chicago these days, with a slew of talented ensembles, musicians and composers.

The Frequency Series, curated by Chicago Reader music critic Peter Margasak, has been presenting concerts of new music on Sundays at Constellation in 2013. Last week, Frequency went a step further, with the first Festival of Chicago New Music. I attended two of the concerts:

Flutist Claire Chase performed Saturday, Feb. 27, at Constellation — but billing her just as a “flutist” is hardly adequate to describe the scope of what she does. Chase, who is a founder of the International Contemporary Ensemble, began this concert standing on a ladder. Over the course of the show, she crawled, jumped and slithered around on the floor, coaxing unexpected sounds from her flutes — including an enormous contrabass flute (pictured below). She also spoke, reciting verse and text, making the whole performance feel like a blend of music and performance art, reminiscent of artists like Laurie Anderson.

This was the latest iteration of “Density 2036,” a 22-year project she launched in 2014 to commission an entirely new body of repertory for solo flute each year until the 100th Anniversary of Edgard Varèse’s groundbreaking 1936 flute solo, “Density 21.5.” Each season between 2014 and 2036, Chase will premiere a new 60-minute program of solo flute work commissioned that year. This concert included the titular work by Varese alongside new pieces by Dai Fujikura, Francesca Verunelli, Nathan Davis, Jason Eckardt and Pauline Oliveros. It was a strange and impressive spectacle.

The Spektral Quartet played Sunday, Feb. 28, at Fullerton Hall in the Art Institute of Chicago, performing two compositions that tested how far musicians can go with the idea of playing string instruments as quietly as possible. The first half of the concert was the premiere of Bagatellen, a sequence of nine short movements by German-born Chicago resident Hans Thomalla. Thomalla’s concept was to take musical fragments and use them as the germinative seeds for each of this pieces. Frankly, I’m not sure how much different that is from the typical way pieces of music originate. But whatever the theory is behind Bagatellen, it was a mesmerizing suite, with some passages so quiet that you had to strain to hear slight tones hiding inside the clicks, buzzes and hums of fingers and bows touching the instruments.

The second half of the concert was Austro-Swiss composer Beat Furrer’s String Quartet No. 3, which employed a similar dynamic range. I had trouble grasping what was going on in this composition. Spektral’s players showed virtuosity, but the music itself left me cold. As with so much “new music” — especially music without traditional melody, harmony and rhythm — it might take many listens to reach a fuller appreciation.

Members of the Spektral Quartet introduced the music with helpful explanations — even demonstrating some of the ideas with brief snippets on their instruments. And at the end of the concert, they sat down along with Hans Thomalla to answer audience questions.

Brötzmann, Drake & Parker at Constellation

The Peter Brötzmann, Hamid Drake & William Parker Trio played Friday night at Constellation — one of the first concerts this improvisational powerhouse has played together since 2004. And it was the first time I had ever seen Brötzmann, a German free-jazz saxophonist. After the band took the stage without uttering a word, and after the welcoming applause died down, Brötzmann paused at his table of reed instruments, as if wondering which one to play. Once he’d strapped a sax around his neck, he silently stood a moment, poised to blow. It was so quiet that I expected the music to begin quietly, but Brötzmann did not ease us into things. He suddenly blurted out a cacophonous blast, pulling us into a complex string of notes in what seemed like midstream. That was just the beginning of a piece that stretched on for something like 40 minutes. Throughout the concert — which the trio performed without taking a set break — Drake’s percussion and Parker’s bass lines gracefully danced around Brötzmann’s forceful, inventive improvisations. It was bracing and dazzling.

Fred Frith at Constellation

Monday night at Constellation, Fred Frith shook and scraped and stroked and beat his guitar. He set a can on top of the strings and ran a red ribbon through them. And that isn’t half of what he did. He had a whole table of implements ready to coax noises out of his guitar. He made it rattle and rumble and ring out. Very little of what came out of the amplifier sounded anything like conventional musical structure, and yet it was undeniably musical. At one point, Frith succeeded in making his guitar sound extraordinarily like a dulcimer.

Near the culmination of Frith’s hourlong improvisation, he sang wordless melodies. And when the whole remarkable performance was over and he left the room and everyone applauded, he came back and gave a bow. The crowd clapped more, and Frith came back one more time. He told us he wouldn’t be playing an encore, because he had just tried to take all of us on a journey with his music.

“We finally get somewhere and what do we do? Get back on the bus and go somewhere else? Nah.”

Ólafur Arnalds at Constellation

Constellation — Mike Reed’s music and arts venue in the old Viaduct Theatre space — has been hosting some interesting concerts since opening earlier this year. So far, it’s living up to its promise as a home for music of various genres outside of the mainstream. Located on Western Avenue’s frontage street, along the stretch where the main part of Western Avenue ascends on a bridge over Belmont, Constellation has a barely noticeable sign identifying the venue. The front door could be mistaken for an entrance into a warehouse. On Thursday night (Oct. 3), the music behind that door was the elegant and spare quasi-classical, quasi-electronic, quasi-indie rock of Icelandic composer and pianist Ólafur Arnalds.

He played two sets that night in the smaller of Constellation’s two performance spaces; I caught the late show. Before he sat down at the piano, Arnalds apologized for being tired, saying he’d flown from San Diego to Chicago around 3 a.m. and had barely slept. He said he’d nodded off three times during the short interlude between his two Constellation performances. “This is a strange place for a concert,” he said, looking around the room, which has the plain, unadorned style of a music or dance rehearsal space. “It’s the smallest place we’ve played in years.” Later in the show, he remarked: “It kind of feels like playing in my living room, which is nice. … It’s like you didn’t pay 30 bucks to see me and I just invited you.” (According to Althea Legaspi’s review for the Chicago Tribune, he made similar remarks at the early concert.)

Arnalds asked the audience to sing a middle C, which he recorded and played back on his iPad, which was sitting on top of the piano. He joked that he could switch out this crowd’s vocals with a prerecorded track if he needed to, and we wouldn’t realize what he’d done — but then he praised us for doing a good job. With that “ah” sustaining in the background, Arnalds began playing the piano.

Throughout the concert, as Arnalds played songs from his latest album, For Now I Am Winter, and other recordings, he kept his hands clustered together near the middle of the keyboard. His right hand seemed to stay in the octave above Middle C, while the left hand stayed in the space just below Middle C, both playing spare, seemingly simple sequences of notes. Arnalds doesn’t appear to be striving for impressive virtuosity; rather, he’s striving to convey his melodies and musical moods in a clear, distilled form. (His website includes free downloadable sheet music of some compositions.)

Violinist Viktor Orri Árnason (of the band Hjaltalín) and cellist Rubin Kodheli accompanied Arnalds, and so did that iPad, which delivered electronic beats, ambient textures and other recorded tracks, without ever overwhelming the live performers. An extended and expressive solo by Árnason was one of the concert’s high points, leaving the strings of his bow shredded by the end. “I guess I have to buy him a new bow,” Arnalds commented.

Vocalist Arnór Dan Arnarson (of the band Agent Fresco) also joined in with the group on a few songs, singing in a high, quivering voice a bit reminiscent of Antony Hegarty. He had apparently just joined the tour. “He wasn’t supposed to be here tonight,” Arnalds said. “He just showed up.”

The audience applauded enthusiastically after Arnalds and his musicians left the room. Finally, he sleepily wandered back in. Someone in the crowd called out, “Sorry!” Arnalds remarked, “I took a while because I fell asleep … It’s very lovely to play when you haven’t slept for 24 hours.”

For his final song of the night, Arnalds played “Lag fyrir ömmu,” which means “Song for Grandma.” As he explained, the song is dedicated to his late grandmother, “the person who got me into this non-death-metal music.” Arnalds was alone now in the performance section of the room, playing on the piano without any accompaniment. Midway through the song, the sound of Árnason’s violin drifted in from the room next door. Árnason did not come back into the room, but his violin solo sounded like a voice calling from the distance. It was a beautiful and touching moment.

Thursday’s concert also included a lovely opening set by Danish singer-songwriter Lisa Alma, whose soft, meditative ballads started out the evening on a sweet note.